Chapter 11: Rent-seeking

Chapter summary

The US National Lobbyist Directory records there to be over 40,000 state registered lobbyists in the USA and a further 4,000 federal government lobbyists registered in Washington. Some estimates put the total number, including those who are on other registers or are unregistered, as high as 100,000. Although the number of lobbyists in the USA dwarfs those elsewhere, there are large numbers of lobbyists in all major capitals. Lobbyists are not engaged in production but instead seek favourable government treatment for the organisations that employ them. The US economy has at least 40,000 individuals who are attempting to influence government policy and shift the direction of income flow. The behaviour that the lobbyists are engaged in is rent-seeking. It uses valuable resources unproductively and can push the government into inefficient decisions. This places the economy within its production possibility frontier and is an explanation for Pareto inefficiency. The chapter considers the nature and definition of rent-seeking. It then proceeds to analyse a simple game that demonstrates the essence of rent-seeking. The insights generated from the game are then applied to rent-seeking in the context of monopoly. This partial equilibrium analysis of monopoly is then extended to a general equilibrium setting. The emphasis is then placed on how and why rents are created. The motives for government to allow itself to be swayed by lobbyists are then detailed. Finally, possible policies to control rent-seeking are considered.

11.1 Definitions

The concept of rent-seeking can be understood by considering the following two examples:

1. A firm is engaged in research intended to develop a new product. If the research is successful, the product will be unique and the firm will have a monopoly position, and extract some rent from this, until rival products are introduced.

2. A firm has introduced a new product to the home market. A similar product is produced overseas. The firm hires lawyers to lobby the government to prevent imports of the overseas product. If it is successful, it will enjoy a monopoly position from which it will earn rents.

In both examples the firm gains a monopoly position from which it can earn monopoly rents. The fundamental difference is that in the first case the firm expends resources to develop a new product which will lead to monopoly rent only if the product is successful. In contrast, the resources used in the second case are reducing economic welfare. If the lawyers are successful, consumers will be denied a choice between products and face higher prices so their welfare is reduced. Although the research and the lawyers are both directed at attaining a monopoly position, in the first case

research increases economic welfare but in the second lawyers reduce it.

These comments allow two concepts to be distinguished.

1. Profit-seeking is the expenditure of resources to create a profitable position that is ultimately beneficial to society.

2. Rent-seeking is the expenditure of resources to create a profitable opportunity that is ultimately damaging to society.

Rent-seeking can take many forms. All lobbying of government for beneficial treatment, be it protection from competition or the payment of subsidies, is rent-seeking. Expenditure on advertising or the protection of property rights is rent-seeking. And so is arguing for tariffs to protect infant industries. These activities are rife in most economies so rent-seeking is a widespread and important issue.

The economic literature has also dealt with the very closely related concept of directly unproductive activities. What distinguishes this from rent-seeking is not always that clear and many economists use them interchangeably. If there is a precise distinction, it is in the fact that directly unproductive activities are by definition a waste of resources whereas rent-seeking may not always involve activities which waste resources. The focus below will be placed on rent-seeking though almost all of what is said could be rephrased in terms of directly unproductive activities.

11.2 A rent-seeking game

The fundamental insight of the analysis of rent-seeking is the Complete Dissipation Theorem: competition for a rent will result in resources being expended up until the expected gain of society from the existence of the rent is zero. This implies that the resources used in rent-seeking are exactly equal in value to the size of the rent. The application of the rent- seeking concept shows that the losses caused by distortions are potentially much larger than the standard measure of deadweight loss.

This section considers a simple game that captures the essential aspects of rent-seeking. The basic structure of the game is as follows. Consider the offer of a prize of $10. Two competitors enter the game by simultaneously placing a sum of money on a table and setting it alight. The prize is awarded to the competitor that burns the most money. Assuming that the competitors are all identical, how much money will each one burn?

Before conducting the analysis, it is worth detailing how this game relates to rent-seeking. The prize to be won is the rent – think of this as the profit that will accrue if awarded a monopoly in the supply of a product. The money that is burnt is the resource used in lobbying for the award of

the monopoly.

The interpretation of the equilibrium of the game is that the two players burn, in total, a sum of money exactly equal to the value of the prize. In social terms, society is ultimately made no better-off by the existence of the prize. The general principle of the example is summarised in the

following theorem.

Complete Dissipation Theorem: If there are two or more competitors, the total expected value of resources expended by the competitors in seeking a prize of value V is exactly V.

11.3 Social cost of monopoly

Monopoly is one of the causes of market failure. A monopolist produces an output below the competitive level in order to raise price and earn monopoly profits. This causes some consumer surplus to be turned into profit and some to become deadweight loss. Standard economic analysis views this deadweight loss to be the cost of monopoly power. The application of rent-seeking concepts suggests that the cost may actually be much greater.

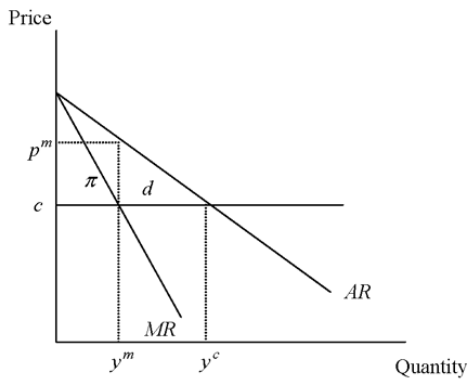

This depicts a monopoly producing with constant marginal cost c and no fixed costs. Average revenue is denoted AR and marginal revenue by MR. The monopoly price and output are p m and y m while the competitive output would be y c . Monopoly profit is the rectangle pi and deadweight loss the triangle d. In a static situation the deadweight loss d is the standard measure of the cost of monopoly.

For both cases, the implications are the same. The value of having the monopoly position is given by the area Pi . If there are a number of potential monopolists bidding for the monopoly, then the analysis of money-burning can be applied to show that the entire value will be dissipated in lobbying. Alternatively, if an incumbent monopolist is defending their position, they will expend resources up to value Pi to do so. In both cases the costs of rent-seeking will be Pi.

Combining these rent-seeking costs with the standard deadweight loss of monopoly, the total cost of the monopoly to society is at least d and may be as high as Pi + d. What determines the total cost is the nature of the rent-seeking activity. If all the rent-seeking costs are expended on unproductive activities, such as time spent lobbying, then the total social cost of the monopoly is exactly Pi + d.

These results demonstrate that considering rent-seeking strongly alters our assessment of the social costs of monopoly – the standard deadweight loss measure seriously understates the true loss. This conclusion does not apply just to monopoly. Rent-seeking has the same effect when applied to any distortionary government policy. This includes regulation, tariffs, taxes and spending. It also shows that the net costs of a distortionary policy may be much higher than an analysis of benevolent government suggests.

• Monopoly profit as rent

• Resources expended to obtain rent

• Welfare loss should include deadweight loss and profit

11.4 Equilibrium effects

The discussion of monopoly welfare loss in the previous section is an example of partial equilibrium analysis. It considered the monopolist in isolation and did not consider any potential spillovers into related markets nor the consequences of rent-seeking for the economy as a whole. This section will extend the analysis to take account of equilibrium effects.

Consider an economy that produces two goods and has a fixed supply of labour. The competitive equilibrium price ratio p^c = p_1 / p_2 determines the gradient of the line tangent to the ppf at point a. This is the equilibrium for the economy in the absence of lobbying.

The lobbying that we consider is for the monopolisation of industry 1. If successful, it will have two effects. The first will be to change the relative prices in the economy. The second will be to use some labour in the lobbying process which could usefully be used elsewhere.

Let the monopoly price for good 1 be given by p_m^1 and the monopoly price ratio by p^m = p_m^1 /p_2 . Since p^m > p^c the monopoly price line will be steeper than the competitive price line. The price effect alone moves the economy from point a to point b around the initial production possibility frontier. The second effect of lobbying can be seen by realising that the labour of lobbyists does not produce either good 1 or good 2 but is effectively lost to the economy – the potential output of the economy must fall. The ppf with lobbying must lie inside that without lobbying.

• Monopoly reduces value of output

• Lobbying shifts the ppf inwards

• Lobbying may raise value of monopoly output

11.5 Rent creation

We now turn to the motives for the deliberate creation of rents. Such rent-creation is important since the existence of a rent implies a distortion in the economy. Hence the economic cost of a created rent is the total of the rent-seeking costs plus the cost of the economic distortion.

It has already been noted that this rent-creation leads to the economic costs of the associated rent-seeking. There are also further costs. The returns from the lobbying - there will be excessive resources devoted to securing these positions. Political office will be highly sought after with

too many candidates spending too much money in seeking election. Bureaucratic positions will be valued far in excess of the contribution that bureaucrats make to economic welfare.

Two further effects arise. Firstly, there will be an excessive number of distortions introduced into the economy. Distortions will be created until there is no further potential for the decision-maker to extract additional benefits from lobbyists. Secondly, there will be an excessive number of

changes in policy. Decision-makers will constantly seek new methods of creating rents and this will involve policy being continually revised.

• Power allows rent creation

• Rents created by selling concessions

• Resources wasted competing for power

11.6 Controlling rent-seeking

Much has been made of the economic cost of rent-seeking. These insights are interesting (and also depressing for those who may believe in benevolent government) but are of little value unless they suggest methods of controlling the phenomenon. This section gathers together a number of proposals that have been made in this respect. There are two channels through which rent-seeking can be controlled. The first channel is to limit the efforts that can be put into rent-seeking. The second is to restrict the process of rent-creation.

Beginning with the latter, rent-creation relies on the unequal treatment of economic agents. Consequently, a first step in controlling rent-seeking would be to disallow policies that discriminate between economic agents. The restriction to the implementation of non-discriminatory policies.

The drawback of a rule preventing discrimination is that sometimes it is economically efficient to discriminate. As an example, the theory of optimal commodity taxation describes circumstances in which it is efficient for necessities to be taxed more heavily than luxuries. Similarly, the theory of income taxation finds that in general it is optimal to have a marginal rate of income tax that is not uniform. If implemented, the taxpayers facing a higher marginal rate would have grounds for alleging discrimination.

There are other ways in which the process of rent-seeking can be lessened but all of these are weaker than a non-discrimination rule. These primarily focus on ensuring that the policy-making process is as transparent as possible. Among them would be responses such as limiting campaign budgets, insisting on the revelation of names of donors, requiring registration of lobbyists, regulating and limiting gifts, and reviewing bureaucratic decisions. Policing can be improved to lessen the use of

bribes. Unlike non-discrimination, none of these policies has any economic implications other than their direct effect on rent-seeking.

• Rent-creation involves unequal treatment

• Non-discrimination rules can prevent this

• Policy process should be transparent

Reading: Jean Hindriks and Gareth D. Myles (2004), Intermediate Public Economics

Chapter 5: Rent-Seeking

• Profit-seeking is the expenditure of resources to create a profitable position that is ultimately beneficial to society. Profit seeking, as exemplified by the example of research, is what drives progress in the economy and is the motivating force behind competition.

• Rent-seeking is the expenditure of resources to create a profitable opportunity that is ultimately damaging to society. Rent-seeking, as exemplified by the use of lawyers, hinders the economy and limits competition. p77

"... rent-seeking can take many forms. All lobbying of government for beneficial treatment, be it protection from competition or the payment of subsidies, is rent-seeking. Expenditure on advertising or the protection of property rights is rent-seeking. And so is arguing for tariffs to protect infant industries." p77

"The economic literature has also dealt with the very closely related concept of directly unproductive activities. The distinction between the two is not always that clear and many economists use them interchangeably. If there is a precise distinction, it is in the fact that directly unproductive activities are by definition a waste of resources whereas the activity of rent-seeking may not always involves activities which waste resources." p78

"Theorem 5 (Complete Dissipation Theorem) If there are two or more competitors in a deterministic rent-seeking game, the total expected value of resources expended by the competitors in seeking a prize of V is exactly V." p81, money burning game

"Theorem 6 (Partial Dissipation Theorem) If there are two or more competitors in a probabilistic rent-seeking game, the total expected value of resources expended by the competitors in seeking a prize of V is a fraction (n − 1)/n of the prize value V, and is increasing with the number of competitors." p83 money burning game

"This fundamental conclusion of the rent-seeking literature shows that the existence of a rent does not benefit society since a significant amount of resources (possibly equal in value to that rent) will be exhausted in capturing it. This conclusion has to be slightly modified with risk aversion. In this case there is less expenditures on rent seeking and thus less rent dissipation. However the expected utility gain of the competition is zero. In welfare terms, society does not benefit from the rent." p85

"Monopoly is one of the causes of economic inefficiency. A monopolist restricts output below the competitive level in order to raise price and earn monopoly profits. This causes some consumer surplus to be turned into profit and some to become deadweight loss. Standard economic analysis views this deadweight loss to be the cost of monopoly power. The application of rent-seeking concepts suggests that the cost may actually be much greater."

p85

This occurs due to competition for the monopoly position (e.g., license).

"The value of having the monopoly position is given by the area π. If there are a number of potential monopolists bidding for the monopoly, then the analysis of money-burning can be applied to show that, if they are risk neutral, the entire value will be dissipated in lobbying. Alternatively, if an incumbent monopolist is defending their position, they will expend resources up to value π to do so. In both cases the costs of rent-seeking will be π. Combining these rent-seeking costs with the standard deadweight loss of monopoly, the conclusion of the analysis is that the total cost of the monopoly to society is at least d and may be as high as π + d." p86

"The discussion so far has presented a picture of lobbyists as a group who contribute nothing to the economy and are just a source of welfare loss. To provide some balance, it is important to note that circumstances can arise in which lobbyists do make a positive contribution. Lobbyists may be able to benefit the economy if they, or the interest groups they represent, have superior information about the policy environment than the decision maker. By transmitting this information to the policy-maker, they can assist in the choice of a better policy." p95