Chapter 7: Externalities

Chapter summary

An externality is a link between economic agents that lies outside the price system of the economy. Everyday examples include the pollution from a factory which harms a local fishery and the envy that is felt when a neighbour proudly displays a new car. Such externalities are not controlled directly by price – the fishery cannot choose to buy less pollution nor can you choose to buy your neighbour a worse car. This prevents the efficiency theorems described in Chapter 2 from applying. The control of externalities is an issue of increasing practical importance. Global warming and the destruction of the ozone layer are two of the most significant examples but there are numerous others, from local to global environmental issues. This chapter shows why market failure arises with externalities and the nature of the resulting inefficiency. The design of the optimal set of corrective, or Pigouvian, taxes is then addressed. Taxes are then contrasted with direct control through tradeable licences. Internalisation as a solution to externalities is also considered. Finally, these methods of solving the externality problem are contrasted to the claim of the Coase theorem that efficiency will be eliminated by trade.

7.1 Externalities defined

Externality: An externality is present whenever some economic agent’s welfare (utility or profit) includes real variables whose values are chosen by others without particular attention to the effect upon the welfare of the other agents they affect.

The definition implicitly distinguishes between two broad categories of externality. A **production externality** occurs when the effect of the externality is upon a profit relationship and a **consumption externality** whenever a utility level is affected. Clearly, an externality can be both a consumption and a production externality simultaneously. For example, pollution from a factory may affect the profit of a commercial fishery and the utility of leisure anglers.

7.2 Market inefficiency

It has been implicit throughout the discussion above that the presence of externalities will result in the competitive equilibrium failing to be Pareto efficient. The immediate implication of this fact is that incorrect quantities of goods, and hence externalities, will be produced. It is also clear that a non-Pareto efficient outcome will never maximise welfare.

Consider a two-consumer economy where the consumers have utility functions

U^1 = U^1 x1_1 , x_2^1 , x_1^1 , (7.3)

and

U^2 = U^2 x1^2 , x_2^2 , x_1^1 . (7.4)

The externality effect in (7.3) and (7.4) is generated by consumption of good 1 by the other consumer. The externality will be positive if U^h is increasing in x_j^1 , h ≠ j, and negative if decreasing.

7.3 The tragedy of the commons

The tragedy of the commons has its origins in the observation that common land would be overgrazed because of negative externalities linking the users.

The implication for government policy is that access has to be controlled, either by a pricing system which takes the negative externality into account or by licensing access to the resource.

7.4 Pigouvian taxation

The description of inefficiency has shown that the basic source of market failure is the divergence between social and private benefits (or between private costs and social costs). A natural means of eliminating such divergence is to employ appropriate taxes or subsidies. By modifying the decision problems of the firms and consumers these can move the economy closer to an efficient position.

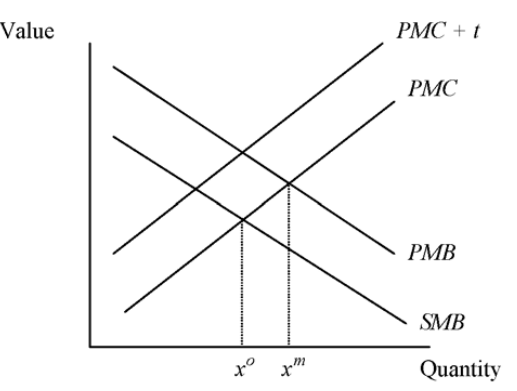

The market outcome can be improved by placing a tax upon consumption. What is necessary is to raise the PMC so that it intersects the SMB vertically above x o . This is what happens for the curve PMC’ which has been raised above PMC by a tax of value t. This process, often termed Pigouvian taxation, allows the market to attain efficiency for the situation shown.

With many consumers the conclusion that a single tax rate could achieve efficiency is misleading. In fact, the general outcome is that there must be a different tax rate for each good for each consumer. Achieving efficiency needs taxes to be differentiated across goods and across consumers. Naturally, this finding immediately shows the practical difficulties involved in implementing Pigouvian taxation. The same arguments concerning information that were placed against the Lindahl equilibrium with personalised pricing are all relevant again here. In conclusion, Pigouvian taxation can achieve efficiency but needs an unacceptable degree of differentiation.

If the required degree of efficiency is not available, for instance information limitations necessitate that all consumers must pay the same tax rate, then efficiency will not be achieved. In such cases the chosen taxes will have to achieve a compromise. They cannot entirely correct for

the externality but can go some way towards doing so.

7.5 Licences

The reason why Pigouvian taxation can raise welfare is that the unregulated market will produce incorrect quantities of externalities. Taxes alter the cost of generating an externality and, if correctly set, will ensure that the optimal quantity of externality is produced. An apparently simpler alternative is to control externalities directly by the use of licences. This can be done by legislating that externalities can only be generated up to the quantity permitted by licences held. The optimal quantity of an externality can then be calculated and licences totalling this quantity

distributed. Permitting these licences to be traded will ensure that they are eventually used by those who have most benefit.

Administratively, there are advantages to licences. As was argued in the previous section, the calculation of optimal Pigouvian taxes requires considerable information. The tax rates will also need to be continually changed as the economic environment evolves.

The fundamental issue involved in choosing between taxes and licences revolves around information. There are two sides to this. The first is what must be known to calculate the taxes or determine the number of licences. The second is what is known when decisions have to be taken. Although licences may appear to have an informational advantage this is not really the case. To calculate the Pigouvian taxes the knowledge of both the preferences and incomes of consumers must be known and, if the model had included production, the production technologies of firms. To determine the optimal level requires precisely the same information as is necessary for the tax rates. Consequently, taxes and

licences are equivalent in their informational demands.

7.6 Internalisation

The externality problem could be resolved by using taxation or insisting that both producers raise their quantities. Although both these would work, there is another simpler solution, through internalisation through mergers.

Internalisation will eliminate the consequences of an externality in a very direct manner by ensuring that private and social costs are equated. However it is unlikely to be a practical solution when many distinct economic agents contribute separately to the total externality and has the disadvantage of leading to increased market power.

7.7 The Coase theorem

Coase theorem suggests that economic agents may resolve externality problems themselves without the need for government intervention.

The Coase theorem: In a competitive economy with complete information and zero transaction costs, the allocation of resources will be efficient and invariant with respect to legal rules of entitlement.

The legal rules of entitlement, or property rights, are of central importance to the Coase theorem. Property rights are the rules which determine ownership within the economy.

The implication of the Coase theorem is that there is no need for policy intervention with regard to externalities except to ensure that property rights are clearly defined. When they are, the theorem presumes that those affected by an externality will find it in their interest to reach private agreements to eliminate any market failure.

When the practical relevance of the Coase theorem is considered, a number of issues arise:

1. Property rights. It is usually clear who is the purchaser and who is the supplier of a standard commodity. This is not the case with externalities.

2. Transaction costs. If the exchange of commodities would lead to mutually beneficial gains for two parties, the commodities will be exchanged unless the transaction costs outweigh the benefits.

3. Market thinness. When external effects are traded, there will generally only be one agent on each side of the market. This thinness of the market undermines the assumption of competitive behaviour that can support the efficiency hypothesis.

Reading: Jean Hindriks and Gareth D. Myles (2004), Intermediate Public Economics

Chapter 10 Externalities

"An externality is a link between economic agents that lies outside the price system of the economy.... a consumer or a firm may be directly affected by the actions of other agents in the economy... In the presence of such externalities the outcome of a competitive market is unlikely to be Pareto efficient because agents will not take account the external effects of their (consumption/production) decisions. Typically, the economy will display too great a quantity of “bad” externalities and too small a quantity of “good” externalities." p195

"An externality is present whenever some economic agent’s welfare (utility or profit) is directly affected by the action of another agent (consumer or producer) in the economy." p196

"A *production externality* occurs when the effect of the externality is upon a profit relationship and a *consumption externality* whenever

a utility level is affected." p196

At the most general level, this assumption implies that the utility functions take the form U^h = U^h (x, y) , h = 1, ..., H, (10.1) and the production set is described by Y^j = Y^j (x, y) , j = 1, ..., m.

"It is immediately apparent from (10.1) and (10.2) that the actions of the agents in the economy will no longer be independent or determined solely by

price.. it becomes apparent why the efficient functioning of the competitive economy will generally not be observed in an economy with externalities." p197

"It has been accepted throughout the discussion above that the presence of externalities will result in the competitive equilibrium failing to be Pareto efficient. The immediate implication of this fact is that incorrect quantities of goods, and hence externalities, will be produced. It is also clear that a non-Pareto efficient outcome will never maximize welfare." p197

"The laissez-faire equilibrium is efficient because the external effect is a change in price and income so that the economists’ cost of a lower income is a benefit to employers. Employers’ benefit equals employees’ cost. There is zero net effect. The policy implication is that there is no need for government intervention to regulate the access to some professions. It follows that any public policy that aims to limit the access to some profession (like the numerus claususis) is not justified. Market forces will correctly allocate the right number of people to each of the different professions." p202

"The rat race problem is a contest for relative position... performance is judged not in absolute terms but in relative terms... The result of this is an inefficient rat race in which each student works too hard to no ultimate advantage. If all could agree to work less hard, the same grades would be obtained with less work. Such an agreement to work less hard cannot be self-supporting since each student would then have an incentive

to work harder." p203

"The rat race problem is present in almost every contest where something important is at stake and rewards are determined by relative position. In an

electoral competition race, contestants spend millions on advertising and governing bodies have now put strict limit on the amount of campaign advertising. Similarly, a ban on cigarette advertising has been introduced in many countries. Surprisingly enough this ban turned out to be beneficial to cigarette companies. The reason is that the ban helped them out of the costly rat race in defensive advertising where a company must advertises because the others do." p204

"Therefore the tax on consumer 1 is the negative of the externality effect on consumer 2 caused by the consumption of good z by consumer 1. Hence if the good causes a negative externality (v 2 0 (z 1 ) < 0), the tax is positive. The converse holds if it is a positive externality." p209

"So what does this say for Pigouvian taxation? Put simply, the earlier conclusion that a single tax rate could achieve efficiency was misleading. In fact, the general outcome is that there must be a different tax rate for each externality-generating good for each consumer. Achieving efficiency needs taxes to be differentiated across consumers... The same arguments concerning information that were placed against the Lindahl equilib-

rium for public good provision with personalized pricing are all relevant again here. In conclusion, Pigouvian taxation can achieve efficiency but needs an unachievable degree of differentiation." p209

"The reason why Pigouvian taxation can raise welfare is that the unregulated market will produce incorrect quantities of externalities. The taxes alter the cost of generating an externality and, if correctly set, will ensure that the optimal quantity of externality is produced. An apparently simpler alternative is to control externalities directly by the use of licences. This can be done by legislating that externalities can only be generated up to the quantity permitted by licences held. The optimal quantity of externality can then be calculated and licences totalling this quantity distributed. Permitting these licences to be traded will ensure that they are eventually used by those who obtain the greatest benefit." p210

"Administratively, the use of licences has much to recommend it. As was argued in the previous section the calculation of optimal Pigouvian taxes requires considerable information. The tax rates will also need to be continually changed as the economic environment evolves. Despite these apparently compelling arguments in favour of licences, when the properties of licences and taxes are considered in detail the advantage of the former is not quite so clear." p210

[Beekeeper and Orchid example] "Imagine the two producers merging and forming a single firm. If they were to do so, profit maximization for the combined enterprise would naturally take into account the externality. By so doing, the inefficiency is eliminated. This method of controlling externalities by forming single units out of the parties affected is called internalization and it ensures that private and social costs become the same. It works for both production and consumption externalities whether they are positive or negative." p214

".. Coase Theorem which suggests that economic agents may resolve externality problems themselves without the need for government intervention. This conclusion runs against the standard assessment of the consequences of externalities and explains why the Coase Theorem has been of considerable interest" p214

"*In a competitive economy with complete information and zero transaction costs, the allocation of resources will be efficient and invariant with respect to legal rules of entitlement.*" p214

"Without clearly specified property rights, the bargaining envisaged in the Coase Theorem does not have a firm foundation: neither party would willingly accept that they were the party that should pay... The existence of transactions costs is often seen as the most significant reason

for the non-existence of markets in externalities." p216

"The efficiency thesis of the Coase theorem relies on agreements being reached on the compensation required for external effects. The results above suggest that when information is incomplete, bargaining between agents will not lead to an efficient outcome." p218

"One of the basic assumptions that supports economic analysis is that of convexity. Convexity gives indifference curves their standard shape, so consumers always prefer mixtures to extremes. It also ensures that firms have non-increasing returns so that profit-maximization is well defined. Without convexity, many problems arise with both the decisions of individual decisions of firms and consumers, and with the aggregation of these decisions to find an equilibrium for the economy.

Externalities can be a source of non-convexity." p218

"There is also a second reason for non-convexity with externalities. It is often assumed that once all inputs are properly accounted for, all firms will have constant returns to scale since behavior can always be replicated. ... the externality is a negative one, it becomes diluted by the increase in other inputs and output must more than double. The firm therefore faces private increasing returns to scale. With such increasing returns, the firm’s profit maximizing decision may not have a well-defined finite solution and market equilibrium may again fail to exist.." p219

"The obvious policy response to the externality problem is the introduction of a system of corrective Pigouvian taxes with the tax rates being proportional to the marginal damage inflicted by externality generation. When sufficient differentiation of these taxes is possible between different agents, the first-best outcome can be sustained but such a system is not practical due to its informational requirements. Restricting the taxes to be uniform across agents allows the first-best to be achieved in some special cases but, generally, leads to a second-best outcome. An alternative system of control is to employ marketable licences. These have administrative advantages over taxes and lead to an identical outcome in conditions of certainty. With uncertainty, licences and taxes have different effects and combining the two can lead to a superior outcome." p220