Chapter 8: Imperfect competition

Chapter summary

The analysis of the economic efficiency showed the significance of the competitive assumption that no economic agent has the ability to affect market prices. Under this assumption, prices act as signals that guide agents and coordinate decisions. Imperfect competition arises whenever an economic agent has the ability to influence prices. It follows from the application of economic rationality that those agents who can affect prices will aim to do so to their own advantage. The first part of this chapter categorises types of imperfect competition and demonstrates the failure of efficiency. This is followed by a discussion of tax incidence and tax design. The effects of specific and *ad valorem* taxes are then distinguished and their role in achieving efficiency is assessed. Other potential policy responses to imperfect competition are then described.

8.1 Market forms

Imperfect competition can arise due to monopoly in product markets and in labour markets. Firms with monopoly power will push price above marginal cost in order to raise their profits. This will reduce the equilibrium level of consumption below what it would have been had the market been competitive and will transfer surplus from the consumers to the owners of the firm. Unions with monopoly power can ensure that the wage rate is increased above its competitive level and ensure a surplus for their members. The increase in wage rate reduces employment and output. [*cough* labour markets are monopsonistic]

Firms can engage in non-price competition by choosing the quality and characteristics of their products, undertaking advertising and blocking the entry of competitors. Each of these activities can be interpreted as an attempt to increase market power and obtain a greater surplus. Their consequence is that the assumptions underlying the theorems of welfare economics are violated and an economy with imperfect competition will not achieve an efficient equilibrium. It then becomes possible that policy intervention can improve upon the unregulated outcome.

• Products may be **homogeneous**, so that the output of different firms is indistinguishable, or **differentiated**, so each firm offers a different

variant. With homogeneous products, there must be a single price in the market.

• Differentiation of products can either be **vertical** (so products can be unambiguously ranked in terms of quality) or **horizontal** (so

consumers differ in which specification they prefer). Equilibrium prices can vary across specifications in markets with differentiated products.

• The firms’ objectives may be to maximise their individual profit or, alternatively, they may collude to maximise joint profits.

• The strategic variables can be price, with the firms choosing the prices they charge, leaving the quantity sold to be set by the market.

Alternatively, the level of output can be chosen with the determination of price left to the market.

• Firms may engage in *non-price competition* using variables other than price to gain profit. For example, firms may compete by choosing the specification of their product and the quantity of advertising used to support it. The level of investment can also be a strategic variable if

this can deter entry by making credible a threat to raise output.

• Entry by new firms may be impossible, so that an industry is composed of a fixed number of firms; it may be unhindered or incumbent firms

may be following a policy of entry deterrence.

8.2 Inefficiency

Imperfect competition is one of the standard cases of market failure which leads to the inefficiency of equilibrium.

[Imperfect competition is normal "actually existing" markets. Perfect competition is a unicorn.]

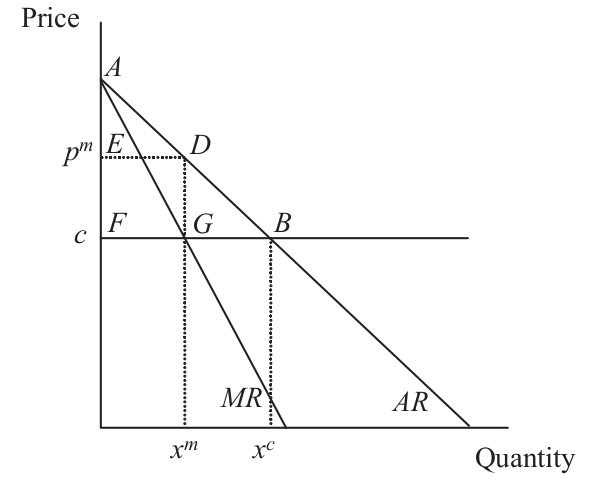

The simplest approach is to contrast market equilibrium with competition to that with monopoly for a given demand and cost structure. Assume that the marginal cost of production for the commodity under consideration is constant at value c and that there are no fixed costs. The equilibrium price if the industry were competitive, p^c , would be equal to marginal cost so p^c = c. This generates the level of consumer surplus shown by ABF. The demand function (also known as the average revenue function) is denoted AR and marginal revenue by MR.

The monopolist’s optimal output, x^m , is determined by the intersection of marginal revenue and marginal cost. At this output, the price is p m , consumer surplus is ADE and profit is DGFE.

Contrasting the competitive and the monopoly outcomes shows that some of the consumer surplus under competition is transformed into profit under monopoly – this is a transfer from consumers to the firm. However, some of it is simply lost. This is the area BGD which is termed the deadweight loss of monopoly. Since the total social surplus under monopoly ADE DGFE is less than under competition ABF, monopoly is inefficient. A reflection of this inefficiency is that consumption is lower under monopoly than competition.

The second way of viewing the inefficiency of imperfect competition is to analyse the firm’s optimisation decision. Continuing the focus on monopoly, let the firm choose output, x, as the strategic variable and retain the assumption that marginal cost remains constant at c. The price obtained with output x is p = phi(x). The firm chooses output to maximise its profit level

pi = p(x) - c(x) = x[phi(x-c)]

The first-order condition that results from this is

phi(x) = x(phi)^1 - c = 0

Since phi^1(x) < 0 (price falls as output increases), the first-order condition implies that p = phi(x) > c = marginal cost. The result in (8.2) shows that the monopolist will set a price above marginal cost and so fails to achieve the standard efficiency condition of price equalling marginal cost.

A final way to demonstrate the inefficiency of imperfect competition is to analyse the problem of choosing output to maximise social benefits. Social benefits can be defined as consumer surplus (the area under the demand curve) less total costs. At output level X^* this is equal to

SB = int phi(X) - c(X)^* (8.3)

Social benefit is then maximised when phi(X)^* - c = 0

which is simply the condition that price equals marginal cost. As shown by (8.2) this condition is not met by monopoly.

• Price is equal to marginal cost with competition

• Price is above marginal cost with imperfect competition

• Imperfect competition results in deadweight loss

8.3 Welfare loss

It has been shown that an imperfectly competitive equilibrium is not Pareto efficient. This observation then makes it natural to consider the extent of welfare loss. The assessment of monopoly welfare loss has been a subject of some dispute in which calculations have provided a range of estimates from the effectively insignificant to considerable percentages of potential welfare.

Contributions to the literature on monopoly welfare loss can be characterised according to three criteria:

• the welfare measure used

• whether data or simulations are employed

• whether the underlying model is of general or partial equilibrium.

8.4 Tax incidence

The analysis of tax incidence determines the changes in prices and profits that follow the imposition of a tax. The formal incidence refers to the party legally required to pay the tax. In contrast economic incidence is concerned with who suffers a loss in welfare (profit or utility) as a

consequence of the tax.

Tax incidence is simple when there is competition and the marginal cost of production is constant. In this case, the supply curve in the absence of taxation must be horizontal at a level equal to marginal cost; see Figure 8.2a. This gives the pre-tax price p = c. The introduction of a tax of amount t will raise the supply curve by exactly the amount of the tax. The post-tax price, q, is determined by the intersection of demand and the new supply curve. It can be seen that q = p t so price will rise by an amount equal to the tax. Hence any taxes are simply passed forward by the firms since price is always set equal to tax-inclusive marginal cost.

When marginal cost is not constant and the supply curve slopes upward, the introduction of a tax still shifts the supply curve vertically upwards by the amount equal to the tax. The extent to which price rises, is then determined by the slopes of the supply and demand curves. If the demand curve is vertical, price rises by the full amount of the tax; otherwise it will rise by less. When it rises by less than the tax, some of the tax is absorbed by the firms and some passed on to consumers.

There is a further surprising outcome that may arise with oligopoly. The total output of an oligopoly will always be greater than for a monopoly, so that total industry profit is lower. A tax increase would be expected to lower profits further. However, a tax increase reduces output which can take the oligopoly closer to the monopoly outcome. For some demand functions this can lead to an increase in the profit levels of all firms.

• Distinction between formal incidence and economic incidence

• Price increase can exceed the tax increase

• Profit may rise when a tax increases

8.5 Efficient taxation

It is now possible to consider the factors that determine the level of commodity taxes with imperfect competition in a simple economy with one competitive and one monopolistic industry. The analysis consists of characterising the direction of tax reform that raises welfare starting from

an initial position with no commodity taxation.

Assume there are two consumption goods. Good 1 is produced with constant returns to scale by a competitive industry and has post-tax price

q_1 = p_1 t_1 . The second good is produced by a monopoly that faces inverse demand

q_2 = phi(x, q_1) (8.6)

The preferences of society are represented by an indirect utility function

U = V(q_1, q_2). (8.7)

The tax reform problem involves finding a pair of tax changes dt_1 , dt_2 that raise welfare whilst collecting zero revenue. If the initial position is taken to be one with zero commodity taxes, the problem can be phrased as finding dt_1 , dt_2 from an initial position with t_1 = t_2 = 0 such that dV > 0, dR = 0, where tax revenue, R, is defined by

R = t_1 x_1 t_2 x_2 (8.8)

This framework ensures that one of the taxes will be negative and the other positive.

The conclusion of this analysis is that the rate of tax shifting is important in the determination of relative levels of taxation. It demonstrates that with imperfect competition commodity taxation can be motivated on efficiency grounds alone.

• Imposition of tax/subsidy can raise welfare

• Subsidise monopoly if price sensitive to taxation

• Finance subsidy by taxing a competitive industry

8.6 Ad valorem and specific taxes

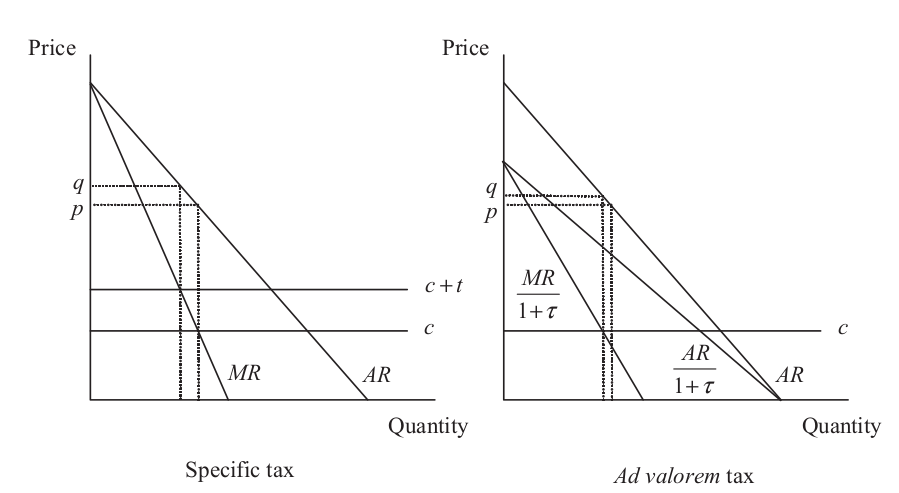

When firms are competitive, specific taxes, which are an addition to the unit costs of production, and ad valorem taxes, which represent a proportional reduction in the received price, have exactly the same effect. That is, for an equal increase in consumer price, they will both raise

the same amount of revenue. The two forms of taxation are therefore equivalent. With imperfect competition this equivalence between the two forms of taxation breaks down.

The argument lying behind this claim is that the ad valorem tax lowers marginal revenue and this reduces the perceived market power of the firm. The ad valorem tax has the helpful effect of reducing monopoly power thus offsetting some of the costs involved in introducing taxes.

• A specific tax affects marginal cost

• An ad valorem tax affects marginal revenue

• The ad valorem tax raises more revenue for a given price

8.7 Regulation of natural monopoly

When faced with imperfect competition, the natural policy response is to encourage an enhanced degree of competition. There are several ways in which this can be done. The most dramatic example is US anti-trust legislation which has enforced the division of monopolies into separate competing firms.

Less dramatic than directly breaking-up firms is to provide aids to competition. A barrier to entry is anything that allows a monopoly to sustain its position and prevent new firms from competing effectively. If a barrier to entry is created by a legal restriction it can equally be removed by a change to the law. But it is necessary to enquire as to why the restriction was created initially [e.g., national strategic advantage].

If barriers to entry relate to technological knowledge, then it is possible for the government to insist upon the sharing of this knowledge. The existence of patents to protect the use of knowledge is also a barrier to entry. The reasoning behind patents is that they allow a reward for innovation. Without patents, the incentive to innovate is reduced and aggregate welfare falls. The policy issue then becomes the choice of the length of a patent. It must be long enough to allow innovation to be

adequately rewarded but not so long that it stifles competition.

The enhancement of competition only works if it is possible for competitors to be viable. The limits of the argument that monopoly should be tackled by the encouragement of competition are confronted when the market is characterised by natural monopoly. The essence of natural monopoly is that there are increasing returns in production and that the level of demand is such that only a single firm can be profitable.

The two policy responses to natural monopoly most widely employed have been public ownership and private ownership with a regulatory body controlling behaviour. When the firm is run under public ownership, its price should be chosen to maximise social welfare subject to the budget constraint placed upon the firm – the resulting price is termed the Ramsey price.

Public ownership was practised extensively in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. All the major utilities including gas, telephones, electricity, water and trains were taken into public ownership. This policy was eventually undermined by the problems of the lack of incentive to innovate, invest or contain costs. Together, these produced a very poor outcome with the lack of market forces producing industries that were over-manned and inefficient.

As an alternative to public ownership, a firm may remain under private ownership but be made subject to the control of a regulatory body. This introduces possible asymmetries in information between the firm and the regulator. Faced with limited information, one approach considered in the theoretical literature is for the regulator to design an incentive mechanism that achieves a desirable outcome.

• Natural monopoly as a barrier to entry

• Public ownership and Ramsey pricing

• Private ownership and regulation

Reading: Jean Hindriks and Gareth D. Myles (2004), Intermediate Public Economics

Chapter 11 Imperfect Competition

"... prices reveal true economic values and act as signals that guide agents to mutually consistent decisions. As the Two Theorems of Welfare Economics showed, they do this so well that Pareto efficiency is attained. Imperfect competition arises whenever an economic agent has the ability to influence prices. To be able to do so requires that the agent must be large relative to the size of the market in which they operate. It follows from the usual application of economic rationality that those agents who can affect prices will aim to do so to their own advantage. This must be detrimental to other agents and to the economy as a whole." p223

"Imperfect competition can take many forms. It can arise due to monopoly in product markets and through monopsony in labor markets. Firms with monopoly power will push price above marginal cost in order to raise their profits. This will reduce the equilibrium level of consumption below what it would have been had the market been competitive and will transfer surplus from consumers to the owners of the firm. Unions with monopoly power can ensure that the wage rate is increased above its competitive level and secure a surplus for their members. The increase in wage rate reduces employment and output." p223

"Imperfect competition arises whenever an economic agent exploits the fact that he has the ability to influence the price of a commodity. If the influence upon price can be exercised by the sellers of a product then there is monopoly power. If it is exercised by the buyers then there is monopsony power, and if by both buyers and sellers there is bilateral monopoly. A single seller is a monopolist and a single buyer a monopsonist. Oligopoly arises with two or more sellers who have market power, with duopoly being the special case of two sellers." p224

"An agent with market power can set either the price at which they sell, with the market choosing quantity, or can set the quantity they supply with the market determining price. When there is either monopoly or monopsony, it does not matter whether price or quantity is chosen: the equilibrium outcome will be the same. If there is more than one agent with market power, then the choice variable does make a difference. Cournot behavior refers to the use of quantity as the strategic variable and Bertrand behavior to the use of prices. Typically, Bertrand behavior is more competitive in that it leads to a lower market price." p224

"The greater the differentiation, the lower the willingness of consumers to switch among sellers when one seller changes its price. The theory of monopolistic competition relates to this competition between many differentiated sellers who can enjoy some limited monopoly power if tastes differ markedly from one consumer to the next." p225

"Markets are also defined by geographic areas, since otherwise identical products will not be close substitutes if they are sold in different areas and the cost of transporting the product from one area to another is large. Given this reasoning, one would expect close competitors to locate as far as possible from each other and it therefore seems quite peculiar to see them located close to one another in some large cities. This reflects a common trade-off between market size and market share. For instance, antique stores in Brussels are located next to one another around the Place du Grand Sablon. The reason is that the bunching effect helps to attract customers in the first place (market size), even if they become closer competitors in dividing up the market (market sharing)." p226

"What does it then mean to say that there is “more” or “less competition” in this market ... The first dimension is contestability that represents the freedom of rivals to enter an industry... A second dimension is the degree of concentration that represents the number and distribution of rivals currently operating in the same market. A widespread measure of market concentration is the n-firm concentration ratio. This is defined as the

consolidated market share of the n largest firms in the market." p226

"The problem with the n-firm concentration index is that it is insensitive to the distribution of market shares between the largest firms... To capture the relative size of the largest firms, another commonly used measure is the Herfindahl index. This index is defined as the sum of the squared market shares of all the firms in the market." p226-227

"The third dimension of the market structure is collusiveness. This is related to the degree of independence of firms’ strategies within the market or its reciprocal which is the possibility for sellers to agree to raise prices in unison. Collusion can be either explicit (such as a cartel agreement) or tacit (when it is in each firm’s interest to refrain from aggressive price cutting)." p227

"The most important fact about imperfect competition is that it invariably leads to inefficiency. The cause of this inefficiency is now isolated in the profit-maximizing behavior of firms who have an incentive to restrict output so that price is increased above the competitive level." p228

"... the monopolist produces with a constant marginal cost, c, and chooses its output level, y, to maximize profit. The market power of the monopolist is reflected in the fact that as their output is increased, the market price of the product will fall.. the monopolist will set price above marginal cost and that the monopolist’s price does not satisfy the efficiency requirement of being equal to marginal cost." p228

"This pricing rule shows that the deviation of price from marginal cost is inversely related to the absolute value of the elasticity of demand. The higher is the absolute value of the elasticity, the smaller is the monopoly mark-up. In the extreme case, if demand were perfectly elastic, which equates to the firm having no market power, then price would be equal to marginal cost." p228

"This relation of the monopoly mark-up to the elasticity of demand can be easily extended from monopoly to oligopoly. Assume that there are m firms in

the market and denote the output of firm j by y_j . The market price of output is now dependent upon the total output of the firms, y = sum y_j. Without output level y_j, the profit level for firm j is p^j [p - c]y_j

".. in the presence of several firms on the market, the Lerner index of market power is deflated according to the market share. As for monopoly, the value of the mark-up is related to the inverse of the elasticity of demand. The Lerner index can be used to show that an oligopoly becomes more competitive as the number of firms in the industry increases. This claim follows from the fact that p−c p must tend to 0 as m tends to infinity. Hence, as the number of firms increases, the Cournot equilibrium becomes more competitive and price tends to marginal cost. The limiting position with an infinite number of firms can be viewed as the idealization of the competitive model." p230

"There is one special case of monopoly for which the equilibrium is efficient. Let the firm be able to charge each consumer the maximum price that they are able to pay. To do so obviously requires the firm to have considerable information about its customers. The consequence is that the firm extracts all consumer surplus and translates it into profit. It will keep supplying the good whilst price is above marginal cost, so total supply will be equal to that under the competition. This scenario, known as perfect price discrimination, results in all the potential surplus in the market being turned into monopoly profit. No surplus is lost due to the monopoly, but all surplus is transferred from the consumers to the firm. Of course, this scenario can only arise with an exceedingly well-informed monopolist." p231

Monopoly inefficiency can also arise from the firm having incomplete information, even in situations where there would be efficiency with complete information....

It has been shown that the equilibrium of an imperfectly competitive market is not Pareto efficient, except in the special case of perfect price discrimination. This makes it natural to consider what the degree of welfare loss may actually be. The assessment of monopoly welfare loss has been a subject of some dispute in which calculations have provided a range of estimates from the effectively insignificant to considerable percentages of potential welfare. p232

"Contrasting the competitive and the monopoly outcomes shows that some of the consumer surplus under competition is transformed into profit under monopoly. This is the area p m BEc and represents a transfer from consumers to the firm. However, some of the consumer surplus is simply lost. This loss is the area BDE which is termed the deadweight loss of monopoly. Since the total social surplus under monopoly (ABp m + p m BEc) is less than that under competition (ADc), the monopoly is inefficient. This inefficiency is reflected in the fact that consumption is lower under monopoly than competition." p233

"From the rent-seeking perspective, the deadweight loss triangle is only one component of the total social cost of monopoly. The rent-seeking literature argues that all the costs of maintaining the monopoly position should be added to deadweight loss to arrive at the total social loss."

p233

"There is one further point that needs to be made. The calculations above have been based upon a static analysis in which there is a single time period. The demand function, the product traded and the costs of production are all given. The firm makes a single choice and then the equilibrium is attained. What this ignores are all the dynamic aspects of economic activity such as investment and innovation. When these factors are taken into account, as Schumpeter forcefully argued, it is even possible for monopoly to generate dynamic welfare gains rather than losses. This claim is based on the argument that investment and innovation will only be undertaken if firms can expect to earn a sufficient return. In a competitive environment, any gains will be competed away so the incentives are eliminated. Conversely, holding a monopoly position allows gains to be realized. This provides the incentive to undertake investment and innovation." p234

"The study of tax incidence is about determining the changes in prices and profits that follow the imposition of a tax. The formal or legal incidence of a tax refers to who is legally responsible for paying the tax. The legal incidence can be very different to the economic incidence which relates to who ultimately has to alter their behavior because of the tax." p235

"When marginal cost is not constant and the supply curve slopes upward, the introduction of a tax still shifts the curve vertically upwards by the amount equal to the tax. The extent to which price rises is then determined by the slopes of the supply and demand curve. If the demand curve is vertical, price rises by the full amount of the tax; otherwise it will rise by less... In summary, if the supply curve is horizontal (so supply is infinitely elastic) or the demand curve is vertical (so demand is completely inelastic), then price will rise by exactly the amount of the tax. In all other cases it will rise by less, with the exact rise being determined by the elasticities of supply and demand. When the price increase is equal to the tax, the entire tax burden is passed by the firm onto the consumers. Otherwise the burden of the tax is shared between firms and consumers." p235-237

"There are two reasons why tax incidence with imperfect competition is distinguished from the analysis for the competitive case. Firstly, prices on imperfectly competitive markets are set at a level above marginal cost. Secondly, imperfectly competitive firms may also earn non-zero profits so taxation can also affect profit. To trace the effects of taxation it is necessary to work through the profit-maximization process of the imperfectly competitive firms. Such an exercise involves characterizing the optimal choices of the firms and then seeing how they are affected by a change in the tax rate." p237

"There is an even more surprising effect that can occur with oligopoly: an increase in taxation can lead to an increase in profit. The analysis of the constant elasticity case can be extended to demonstrate this result. Since the equilibrium price is q = μ o [c + t] , using the demand function the output of each firm is (11.11) Using these values for price and output results in a profit level for each firm of (11.12) The effect of an increase in the tax upon the level of profit is then given by (11.13)... When the elasticity satisfies this restriction, an increase in the tax will raise the level of profit. Put simply, the firms find the addition to their costs to be profitable... It should be observed that such a profit increase cannot occur with monopoly, because a monopolist must produce on the elastic part of the demand curve" p238

"The analysis of tax incidence has so far considered only specific taxation. With specific taxation, the legally-responsible firm has to pay a fixed amount of tax for each unit of output. The amount that has to be paid is independent of the price of the commodity. Consequently, the price the consumer pays is the producer price plus the specific tax. This is not the only way in which taxes can be levied. Commodities can alternatively be subject to ad valorem taxation, so that the tax payment is defined as a fixed proportion of the producer price. Consequently, as price changes, so does the amount paid in tax." p241

"The specific tax leads to an upward shift in the tax-inclusive marginal cost curve. This moves the optimal price from p to q. The ad valorem tax leads to a downward shift in marginal revenue net of tax.... The ad valorem tax leads from price p in the absence of taxation to q with taxation. The resulting price increase is dependent on the slope of the marginal revenue curve." p242

"In conclusion, ad valorem taxation is more effective than specific taxation when there is imperfect competition. The intuition behind this conclusion is that the ad valorem tax lowers marginal revenue and this reduces the perceived market power of the firm. Consequently, the ad valorem tax has the helpful effect of reducing monopoly power, thus offsetting some of the costs involved in raising revenue through commodity taxation." p243

"The enhancement of competition only works if it is possible for competitors to be viable. The limits of the argument that monopoly should be tackled by the encouragement of competition are confronted when the market is characterized by natural monopoly. The essence of natural monopoly is that there are increasing returns in production and that the level of demand is such that only a single firm can be profitable." p245

"What this argument shows is a market in which one firm can be profitable but which cannot support two firms. The problem is that the level of demand

does not generate enough revenue to cover the fixed costs of two firms operating. The examples that are usually cited of natural monopolies involve utilities such as water supply, electricity gas, telephones and railways where a large infrastructure has to be in place to support the market and which would be very costly to replicate." p245

"The two policy responses to natural monopoly most widely employed have been public ownership and private ownership with a regulatory body controlling

behavior. When the firm is run under public ownership, its price should be chosen to maximize social welfare subject to the budget constraint placed upon the firm - the resulting price is termed the Ramsey price. The budget constraint may require the firm to break-even or to generate income above production cost. Alternatively, the firm may be allowed to run a deficit which is financed from other tax revenues. Assume all other markets in the economy are competitive. The Ramsey price for a public firm subject to a break-even constraint will then be equal to marginal cost if this satisfies the constraint. If losses arise at marginal cost, then the Ramsey price will be equal to average cost. The literature on public sector pricing has extended this reasoning to situations in which marginal cost and demand vary over time such as in the supply of electricity. Doing this leads into the theory of peak-load pricing. When other markets are not competitive, the Ramsey price will reflect the distortions elsewhere in the

economy." p246

"Public ownership was practiced extensively in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. All the major utilities including gas, telephones, electricity, water and trains were taken into public ownership. This policy was eventually undermined by the problems of the lack of incentive to innovate, invest or contain costs. Together, these produced a very poor outcome with the lack of market forces producing industries that were over-manned and inefficient." p246-247

"The treatment of the various industries illustrates different responses to the regulation of natural monopoly. The water industry is broken into regional suppliers which do not compete directly but are closely regulated. With telephones, the network is owned by British Telecom but other firms are permitted access agreements to the network. This can allow them to offer a service without the need to undertake the capital investment. In the case of the railways, the ownership of the track, which is the fixed cost, has been separated from the rights to operate trains, which generates the marginal cost. Both the track owner and the train operators remain regulated. With gas and electricity, competing suppliers are permitted to supply using the single existing network." p247

"In oligopolistic markets firms can collectively act as a monopolist and are consequently able to increase their prices. The problem for a regulatory agency is that such collusion is often tacit and so difficult to detect. However, from an economic viewpoint, there is no real competition and a high price is the prima facie evidence of collusion." p248

"As well as monopoly on product markets, it is possible to have unions creating market power for their members on input markets. By organizing labor into a single collective organization, unions are able to raise the wage above the competitive level and generate a surplus for their members." p250

"This inverse pricing rule says that the percentage deviation from the competitive wage is inversely proportional to the elasticity of labor supply. By contrast with the monopoly, the key elasticity is the supply elasticity. Just as monopoly results in a deadweight loss, so does monopsony leading to underemployment and under-pricing of the input (in this case labor) relative to the competitive outcome." p253